Download this curriculum (PDF)

Overview for Teachers

Welcome to Douglass Day 2026! Every year we gather across the country and the world to celebrate the life and legacy of Frederick Douglass by transcribing texts produced by nineteenth century Black people whose work might not be as accessible without our efforts. Thank you for joining us with your students in this important work. This year we will be transcribing the texts generated for, about, and by the Colored Conventions which took place during the Reconstruction era. The background materials we have assembled with their associated lesson plans will teach your students about the context, events, decisions and conditions which shaped the history of that time and consequently the America we live in today.

This curriculum is meant to support your efforts to teach relevant, standards-based content to your students as you prepare them to participate in Douglass Day 2026. In addition, these lessons are meant to offer you the opportunity to explore these concepts across several days within a semester, or to simply grab an activity or idea that works for you and your students on Douglass Day or beyond. There is a prior Douglass Day lesson plan series which prepares your students to transcribe 19th century archives.

In order to set the groundwork for transcribing Reconstruction era conventions, we needed to briefly contextualize a number of topics: American colonial history, The American Civil War, Reconstruction, Homesteading, the Exoduster Movement, Dred Scott, the American Constitution, and Constitutional Amendments. We have provided this material because it is difficult to discuss why the 14th and 15th Amendments are so important without first setting this groundwork. You choose how you approach these topics in your room. We suggest taking a long-term approach or even starting with the 14th and going backwards to fill in the historic information as a strategy. However you approach it, students should understand how and why the 14th Amendment was a necessary choice for post Civil War America and continues to be important today.

If you choose to use this curriculum as a unit plan, it would be ideal to store student work online or in a paper portfolio. At the conclusion of the unit, students will have a folder that will contain all of their work on this topic that they will be able to take home and or share with their family.

We look forward to hearing from you and your experiences with the materials. Please email us at douglassdayorg@gmail.com and specify ‘Curriculum’ in the subject line. Thank you!

Themes: citizenship, identity, race, equal protection, democracy, civil rights, home, activism, agency.

Background: Citizenship and Belonging in the Colored Conventions Movement

In 1830, Black intellectual activists organized the Colored Conventions Movement in Philadelphia to strategically declare and demand their rights as American citizens. Black people brought to, living in, and born in America experienced a hard and often ugly history defined by denial, pain and oppression. Yet America was theirs: by birth, through bloodshed, and as a legacy of their determination and labor. The struggle that Black people and the Colored Conventions activists who worked on their behalf faced was to make America home.

In the records of the Colored Conventions Movement, we find men and women making several calls to the American public, to politicians, and to religious leaders. Activists called for access to education, access to the ballot box, access to protection from and by the state, access to the jury box, fair pay for fair work, freedom from violence, freedom of mobility, and much more. In their calls we find not just the roots of the modern Civil Rights Movement, but the cry of a people denied the right to live in peace in their own homes. Using speeches, lectures, essays, poems, sermons, and songs, Colored Conventions activists repeatedly identified themselves as citizens, and based their claims for freedom, fairness and justice on full citizenship.

In spite of the fact that America defined citizenship only for white men and their children in the 1790 Naturalization Act, Black activists kept demanding full citizenship. Legally, free white men could become citizens after living in America for two years and their children would be eligible for citizenship if they were born in another country. In opposition to English common law on which many American laws are based, American politicians created a citizenship process which depended on whiteness, maleness, and status. Early white politicians created a system that was unfair, oppressive, and immoral. By calling for birthright citizenship, Black activists were pushing America to actually become a real democracy.

By claiming rights of citizenship by birth, Colored Conventions activists insisted that American citizenship be defined by birth –where one was born– and not by blood– who your parents were or where your parents were born. Birthright citizenship, (like the English common law of Jus Soli) legitimized African American claims to citizenship by rejecting citizenship based on race or status. Free and unfree Black people were descendants of enslaved people. Though free, the legal, social, and civil status of Black people was defined by race and their former status as enslaved. Black activists were fighting to change laws, practices, and minds when they demanded their rights as citizens. Colored Conventions activists published letters and articles in newspapers, drew up petitions, gave speeches, presentations, wrote books, essays, poems, and novels in support of Black citizenship.

Black activists claimed and enacted birthright citizenship in Colored Conventions records and in public discourse. This strategic intervention shaped not just the ways African Americans thought about themselves as citizens of America, but more importantly how determined they were to shape American citizenship. As a new country made up of four major colonizers, several indigenous nations, multiple immigrants from as many countries, numerous languages, races, ethnicities, cultures, and religions, the newly formed American nation had to determine the principles, ideas and values that would organize and define it. Citizenship establishes the relationship between individuals, groups of people, their own government, as well as the governments of other countries and nations. Birthright citizenship defines citizenship as a right of birth–not by race, gender, ethnicity, religion, creed, or country of origin. As a concept, birthright citizenship is fair and equally accessible by anyone without exception. Black activists knew this and claimed their birth given citizenship consistently.

Birthright citizenship is the basic principle upon which a fair multi-racial democracy stands. No one is denied access to citizenship as a consequence of factors outside of their control: race. ethnicity, religion, class, gender, or where one’s parents were born. Instead, citizenship is defined by birth. Colored Conventions activists knew that if Black people, the descendants of formerly enslaved people were legally recognized as American citizens, this would address a fatal weakness in the American constitution which made whiteness as a necessary condition of citizenship — in spite of the fact that America was always already multi-racial. Birthright citizenship would acknowledge what was already true about America, versus perpetuate and strengthen the lie of white supremacy. It would only be through reconstructing the nation that the sins, oppression, and unfairness which marked American history could be addressed going into the future. Colored Convention activists worked diligently to define, explain, and demand that America become a truly democratic nation and birthright citizenship is a core principle which made this possible. However, the steady process which had been made by African American activists towards citizenship was stopped by the Supreme Court decision rendered in response to the Dred Scott case.

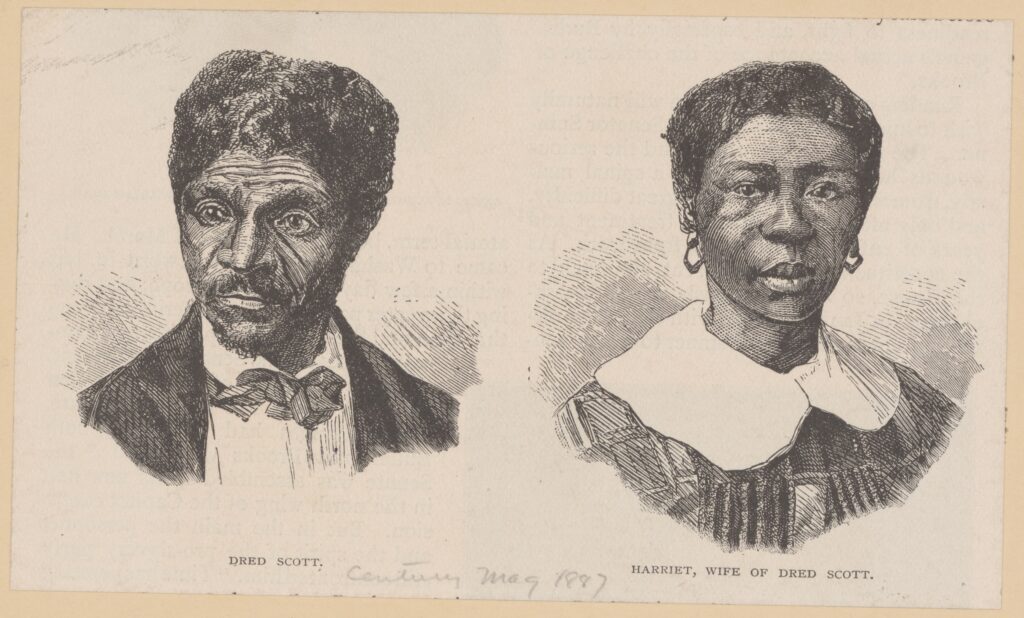

Dred Scott

In 1857, Dred Scott, who had been enslaved all of his life, tried to sue for his freedom after living in states where slavery was illegal. Scott lost and the Supreme Court ruled that as an enslaved Black man, he was not a citizen and therefore had no right to be heard in federal court. The court also declared that Congress could not legally prohibit slavery in U.S. territories and that African Americans were not, and could never be, citizens. This ruling, which upheld slavery and deemed Black people as inferior to white people also invalidated the Missouri Compromise and the Kansas-Nebraska Act by claiming that the government overstepped its rights by interfering with state’s rights to have slavery–which expanded the number of slave states and intensified sectional tensions, bringing the nation closer to a bloody Civil War. Giving this decision, Supreme court Justice Taney famously opined “the Black man had no rights which a white man was bound to respect.” The wildly unfair and deeply disrespectful stance Taney and the majority of the Supreme Court justices took signaled the terrible resistance which Black activists faced in their work to make America a democratic nation. With this ruling, American citizenship in defiance of history, legal precedence, and morality was dependent on white skin.

Activists and abolitionists understood that the color-line, legally, socially, and civilly prevented Black people from the responsibilities and rights of citizenship. The passage of the 1866 Civil Rights Act could have secured the rights of all citizens in America, but it was vetoed by President Johnson. Prior to the failure of the Civil Rights Act, activists had hoped that the abolition of slavery and passage of laws prohibiting racism and oppression would be effective to protect Black people and other non-whites from violence and oppression. After the failure of the Civil Rights act, they realized that the changes necessary to bring America into alignment with the principles of freedom and democracy would require something stronger than laws. Activists and politicians agreed to conceive, develop, and pass the strongest possible tool of freedom—an amendment to the constitution. Look carefully at the clauses in the 14th Amendment. What you will see are the very careful ways that American citizenship was defined and enshrined in the constitution to prevent a biased, unfair, unjust standard of citizenship to ever be imposed again. The 14th Amendment is the foundation of a multi-racial democracy reflecting who we are in fact and in aspiration.

Vocabulary

| Due Process Clause | This clause forces the recognition/enforcement of the Bill of Rights on individual states. What this means is that states cannot violate this set of individual rights without following fair legal procedures. The Supreme Court has also interpreted it to protect “substantive” rights, such as the right to privacy. |

| Enforcement Clause | Gives Congress the power to enforce its provisions through “appropriate legislation,” providing a mechanism for federal oversight and action against states that violate constitutional guarantees. This clause gives the government the power to send in federal forces when states do not follow the law. |

| Equal Protection Clause: | This clause ensures that laws are applied fairly and equally to all people. It has been a crucial legal tool for dismantling segregation (e.g., in Brown v. Board of Education), challenging discrimination in public spaces—including the American with Disabilities Act, and promoting equality in various aspects of American life. |

| Citizenship Clause | The Citizenship Clause was ratified after the Civil War and established birthright citizenship which overturned the Dred Scott decision—the legal decision which denied citizenship to Black people. This clause guarantees that American citizenship is not dependent on race or where someone was born. This clause is the basis of America’s multi-racial democracy. |

| Civil Rights | The rights of citizens to political, social, and legal equality. |

| Democracy | A government elected by citizens to represent all the citizens |

| Supreme Court | The highest court in a country or a state. In America, we have 9 judges who are appointed for life. The decisions made in the Supreme Court make laws (precedents) that all states must follow. |

| Constitution: | The highest law of the land written in a document that established the framework of the U.S. Government and guarantees the rights of its citizens. |

| Primary Source | original documents/objects that were created by the person(s). |

| Transcribe | write/type/transfer data into a written form. |

Standards

Elementary School:

Use information gained from illustrations (e.g., maps, photographs) and the words in a text to demonstrate understanding of the text (e.g., where, when, why, and how key events occur).

Middle School:

Integrate visual information (e.g., in charts, graphs, photographs, videos, or maps) with other information in print and digital texts.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.WHST.6-8.1.B

Support claim(s) with logical reasoning and relevant, accurate data and evidence that demonstrate an understanding of the topic or text, using credible sources.

High School:

Evaluate various explanations for actions or events and determine which explanation best accords with textual evidence, acknowledging where the text leaves matters uncertain.

Integrate and evaluate multiple sources of information presented in diverse formats and media (e.g., visually, quantitatively, as well as in words) in order to address a question or solve a problem).

Essential Questions

- What does it mean to be a citizen?

- Why did America decide birthright citizenship was important?

- What were the claims, arguments, and evidence used to support birthright citizenship?

- What are the challenges in a muti-racial democracy?

- How do we protect the rights that are granted by the Constitution?

Materials and Resources

Resources

Journal Articles

- Sanderfer, Selena. “Tennessee’s Black Postwar Emigration Movements, 1866—1880.” Tennessee Historical Quarterly, vol. 73, no. 4, 2014, pp. 254–79. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43826056.

- Woods, Randall Bennett. “The First Frontier: Kansas and the Great Exodus.” A Black Odyssey: John Lewis Waller and the Promise of American Life, 18781900, University Press of Kansas, 2021, pp. 19–40. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1p2gjrc.8.

- Riley, Glenda. “American Daughters: Black Women in the West.” Montana: The Magazine of Western History, vol. 38, no. 2, 1988, pp. 14–27. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4519131.

- Miles, Tiya. “Beyond a Boundary: Black Lives and the Settler-Native Divide.” The William and Mary Quarterly, vol. 76, no. 3, 2019, pp. 417–26. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.5309/willmaryquar.76.3.0417.

- Hosbey, Justin. “‘I Looked With All The Eyes I Had’: Black Women’s Vision And The Stakes Of Heritage In Nicodemus, Kansas.” Urban Anthropology and Studies of Cultural Systems and World Economic Development, vol. 45, no. 3/4, 2016, pp. 303–47. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/26384875.

- Sargent, Lyman Tower. “African Americans and Utopia: Visions of a Better Life.” Utopian Studies, vol. 31, no. 1, 2020, pp. 25–96. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.5325/utopianstudies.31.1.0025.

Newspaper articles

- The Dredd Scott Dissent Lincoln Loved. New York Times August 8, 2025 by Jamelle Bouie,http://archive.today/VrRnN

- The Last All Black Town in the West. Daily Yonder, March 2024 https://dailyyonder.com/the-last-all-black-town-in-the-west/2024/03/20/

Websites

- Colored Conventions Project https://omeka.coloredconventions.org/

- iCivics— Founded in 2009 by former Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, provides high-quality, nonpartisan civics education resources to educators and students across the United States. A series of iCivics videos is linked to this curriculum.

- Dredd Scott https://dredscottlives.org/dred-scott/

- Nicodemus Historical Society https://www.nicodemushistoricalsociety.org/

- Kansas Black Framers Association https://kbfa.org/

- The Exodusters: African American Migration to the Great Plains exhibit from the Digital Public Library https://dp.la/primary-source-sets/exodusters-african-american-migration-to-the-great-plains

Videos

- Bleeding Kansas episode 1 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-YEC3h4TSX8

- Bleeding Kansas episode 2 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0AxnRj33uac

- Bleedings Kansas episode 3 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q-NeV-BQZIU

- Bleeding Kansas episode 4 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lOUQ6BYhldo

- Bleeding Kansas episode 5 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wTd1nz5siwg&t=10s

Elementary Lessons

Day 1

- Introduce Douglass Day and the life of Frederick Douglass using the Biography of Frederick Douglass for Kids: American Civil Rights History for Children. Students should use a 3-2-1 strategy to take notes.

- Debrief: Why is Frederick Douglass important to American history? Why should he be celebrated?

Day 2

- Introduce the theme for Douglass Day: A Call for Home. Ask students to define the concept of home.

- Students should complete a graphic organizer that demonstrates the different ways home can be defined (ie – where they live with their families, their neighborhoods or city, etc). Students should share their responses.

- Discuss as a class: What does it mean to not have a home? What should be done if people don’t have homes?

Day 3

- Review the prior day’s discussion and introduce the concept of being a citizen. Ask: How are citizens protected in their home country? What happens when they are not?

- Explain that the Constitution is the law of our country and it protects citizens. Use the New Rules for a New Home Presentation to explain key concepts.

- In small groups, students should be assigned an amendment or a clause and not share it with the class. They should develop a short role play that demonstrates when the rules are upheld and the rule is broken. The class should try to guess which rule is being demonstrated.

- Review with the class: Which of these is most important in your life?

Days 4-5

- Individually or in pairs, students should complete the “A Home for All” Model House Project, incorporating the elements of the prior days’ activities. Students’ models should address what would make America feel like home for all its citizens.

Extension Activity

- Create a neighborhood of the model homes within the classroom, and ask students to give tours to other students and community members.

Middle School Lessons

Days 1 – 2

- Introduce Douglass Day and the theme for the year: the 14th Amendment. Ask students to consider the phrase: “A Call for Home,” and freewrite what they believe the phrase means. Discuss responses.

- Explain that students will need to review some key concepts from the Constitution. Students should watch short Quizlet videos, School House Rock – The Constitution, and/or These United States: A History of the Constitution from CBS Sunday Morning and complete the Student Activity: An Overview of the Constitution.

- Students should create a digital quiz or flashcards of key terms and practice with their peers.

Days 3-4

- Introduce Dred Scott using the PBS American Experience Video and the Discussion Questions included on the website.

- Students should read and annotate Student Background: Dred Scott.

- Discuss: What did this mean for citizenship for African-Americans? Was the United States still a ‘home’ for African Americans?

- Students should read and annotate Student Background: American Civil War and Reconstruction. Review the Reconstruction Amendments with students.

- Discuss: What is the connection between the Dred Scott decision and the 14th Amendment? Why is the 14th Amendment important today?

Days 5-7

- Students will view the Vox video on Birthright Citizenship. Discuss: What are the arguments against birthright citizenship? How have the arguments against birthright been connected to immigration?

- Students will research and create a social media campaign that explains citizens’ rights under the 14th Amendment and how they can protect them using the 14th Amendment Social Media Campaign Project.

Extension Activity:

Create a presentation on other Supreme Court cases that demonstrate the importance of the 14th Amendment.

High School Lessons

Day 1

- Introduce students to Douglass Day using the background information included in the unit plan, and ask students to discuss the meaning of “home.” Provide an overview of the Colored Conventions as a political and intellectual movement among African Americans before and after the Civil War.

Days 2-3

- Students should complete the Student Reading: Homesteading and the Exodustuster Movement

- Students will explore the Exoduster Movement beginning with the video, Pap Singleton: To Kansas!, and the included discussion questions from the PBS website or students may complete one or more primary source activities from The Exodusters: African American Migration to the Great Plains exhibit from the Digital Public Library.

- Exit Ticket: What encouraged African Americans to see the possibility of home in Kansas?

Day 4

- Students will engage in primary source analysis using Colored Convention records from the Proceedings of the Colored Convention of the State of Kansas, Held at Leavenworth, October 13th, 14th, 15th, and 16th, 1863.

Days 5-7

- Ask students to list and describe their favorite games. In pairs, students should discuss what makes a game fun and fair. In addition, students should discuss games they don’t like.

- Teacher should introduce key features of game theory using the video, How Decision Making is Actually Science: Game Theory Explained. Discuss how these theories might be applied to history. Considering the experiences of the Exodusters, how would you describe the players, strategies, rules, and referees of this group?

- In groups, students will plan and develop a game that takes players through the experiences of a family moving west during the Exoduster movement using the The Exoduster Game Design Project.

College and University Activities

Community College and University:

Option 1: Write a research paper based on what you have learned about games and the structures of games, referees and players using Game theory. Use a personal example and an example from the histories you have read and now understand about countries and governments. Must include a member of the Colored Conventions who participated in the Exoduster Movement.

Option 2: University: Research a Colored Convention activist and their family, write an argument based essay on them, their choices and their presence in the historical record. Your audience for this paper is a local historical society. Include three primary sources, three secondary sources including images and maps, and two critical articles/journals that explore game theory.

Common Methods for the College Classroom

Note: the suggestions below are common methods used by instructors in college-level classes. Please see the sections above for materials tailored to this year’s theme & project.

Transcribe in Class

Consider dedicating at least one hour in your class for students to hold a transcribe-a-thon. We find that the activities can range in time, but it is usually best to reserve at least an hour in total.

Transcribing a full page usually takes at least ~20-30 minutes. We highly recommend saving some time at the end of the activities for students to share their experiences.

Sample Discussion Questions

- What did you find in the documents?

- What did you find surprising or challenging?

- If you worked on multiple documents, did you notice any recurring patterns or themes?

- What do you feel you learned about the processes of digitization, transcription, and preservation of Black histories?

- How would you encourage other people to try out these activities?

- How do these materials relate to our current moment?

Transcribe in Pairs

We recommend having students transcribe in pairs. Working in pairs will make the experience more collaborative and interactive. Students can support each other in the process of deciphering the historical documents, and that process often leads to rich discussions during the process. (This strategy is especially useful if students are less comfortable with any manuscripts and cursive handwriting.)

Transcribe Outside of Class

If you don’t have time to transcribe together in class, we find that transcribing can be an engaging assignment outside of class. Ask students to transcribe a single page, and then respond to some of the questions above.

If students create an account on the transcription platform, they will be able to see the activity logs for their accounts. After they complete a page or two, they can take a screenshot and send it to you for credit. (Please note that the platform managers are often unable to access that private/personal data so you will need to ask students to self-report.)